In this installment of our “Patterns of Service-oriented Architecture” series, we’re going to talk about a complex concept called idempotency, and a technique you can apply to your service design to ensure that requested work is only performed once.

Intent

Prevent duplicate requests by allowing the Consumer of a Service to send a value that represents the uniqueness of a request, so that no request with the same unique value is attempted more than once.

Motivation

It’s possible—and likely—for a service to perform operations that cannot be undone. For example, charging a customer money cannot be cleanly rolled back once completed. For Services like this, Consumers of the Service need a way to be absolutely sure that their request of that Service had exactly one effect. Stated another way, the service’s calls should be idempotent.

The problem is that the Service might not know enough to ensure idempotence. For example, if a customer makes two purchases for the same amount, the Server can’t tell if this is really two purchases, or if a single purchase is being retried (e.g. due to a network failure that caused the first to get interrupted).

In order to ensure idempotency, the Server would need to know a lot about the use-cases of its Consumers. Instead, the Consumer can provide a unique identifier for each unique interaction. For example, if each purchase has a unique id, the Consumer can pass that id along with the purchase request. The Server will then make sure it does not service the same request twice.

In the purchasing example, suppose there was only one purchase, and the Consumer was interrupted and tried again, using the original purchase ID. The Server can locate the previous request, based on the Consumer’s ID and return the results.

This Consumer-generated ID is an idempotency key.

Applicability

When a dangerous or difficult-to-undo operation must be performed, but it cannot be made idempotent without more context, use an Idempotency Key. Common examples are when creating data in a third-party where that data has a cost, or cannot be easily removed or changed to handle intermittent failures.

Structure

This is a difficult pattern to get right, as each Consumer of a service must properly and carefully design its key. It also requires careful implementation in the service to ensure that the operation of writing the idempotency key and performing the work are themselves idempotent.

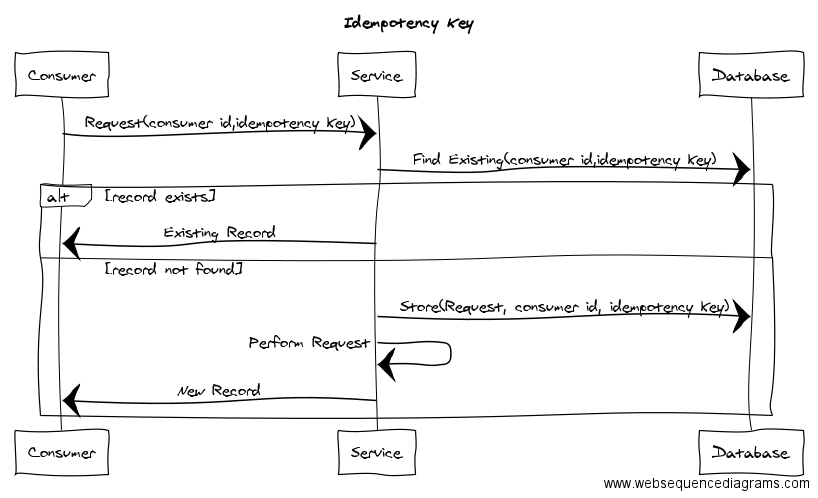

In words:

- A Consumer makes a request. It passes along both an identifier of who it is (e.g. per-consumer API Key) and an idempotency key. Semantically, this means “if you get a request with this idempotency key from me, consider it the same as any other request from me with that idempotency key”.

- The service examines its database for previously-serviced requests from this consumer with the given idempotency key. It’s important that the idempotency key be scoped to a particular consumer, because it’s not possible for all consumers to ensure their idempotency keys are collectively unique.

- If an existing record/response is found, the Service returns that.

- If not, the Service should both store the Consumer ID/idempotency key for later and service the request. This operation must itself be idempotent. You want to avoid a situation where you record a consumer id/idempotency key but don’t do the work (or vice versa). The simplest way to accomplish this is with a Database Transaction.

- Once the work is complete, the new response is returned to the Consumer.

Idempotency Key Algorithm

To make this pattern work, you must choose the right algorithm for calculating your idempotency key. Always remember what you are trying to prevent. You don’t want the same logical operation to be actually performed more than once.

Getting the right algorithm will require playing-out scenarios to see what will happen. Start with playing out the scenarios with no idempotency key:

- Single operation succeeds, response fails, Consumer tries again, what happens?

- Operation fails, response fails, Consumer tries again, what happens?

- Operation succeeds, response succeeds, but Consumer fails after the response, what happens?

From there, replay the scenario with different key algorithms. Start simple, such as the primary key of something being operated on. Often you’ll need to incorporate a time component, for operations that are legal multiple times, but not multiple times in quick succession. You can account for this by adding days or weeks between retries in your scenario and playing out what would happen versus what should happen.

Anti-patterns/Gotchas

- Consumers should almost never re-use the idempotency key algorithm used by other Consumers. Each Consumer must design an idempotency key for their specific use-case. If two Consumers have the same algorithm, it could indicate that one or both algorithms are wrong. The best way to avoid this is to derive your idempotency algorithm from scratch—don’t start with a copy of another one.

- Neither the Service nor Consumer should parse additional meaning from the idempotency key. For example, if your key has a timestamp in it, no logic should exist that parses that timestamp.

- That being said, unnecessarily obfuscating the key’s components can make debugging difficult. You may be tempted to hash the idempotency key, but doing so has little value and makes it hard to back out how the key came to be if there is a problem.

- Log when the idempotency key was used to locate an existing transaction. This will help if you have a poorly-designed idempotency key algorithm, because you can see when the service located existing records.

See Also

- Asynchronous Transaction

- Background Jobs

- Database Transaction

- Idempotent Operations (to be written)