Amazing products without engaged clients are bound to fail, and companies claiming to have found the single best solution to client engagement are only fooling themselves.

What seems to work today to keep your clients engaged won't necessarily work tomorrow. The "optimal" client engagement tactic for your product will change over time and companies must be fluid and adaptable to accommodate ever-changing client needs and business strategies. Becoming complacent by settling for a strategy that works "for now" or "well enough" leads to risk aversion and unrealized potential. Constant recalibration is crucial, yet exploration can be costly and may lead nowhere. A principled approach to finding the right client engagement tactics at any point in time is essential.

Enter, Bandits!

Here at Stitch Fix, we prioritize personalization in every communication, interaction, and outreach opportunity we have with clients. Contextual bandits are one of the ways we enable this personalization.

In a nutshell, a contextual bandit is a framework that allows you to use algorithms to learn the most effective strategy for each individual client, while simultaneously using randomization to continuously track how successful each of your different action choices are.

Implementing a contextual-bandit-based client engagement program will allow you to:

- Understand how the performance of your tactics change over time;

- Select a personalized tactic for each client based on his or her unique characteristics;

- Introduce new tactics relevant to subpopulations of clients in a systematic manner; and

- Continuously refine and improve your algorithms.

Part 1: There are Significant Limitations to Typical Client Engagement Approaches.

Let's set up a simple, clear example.

Current state: There are a group of individuals who have used your product in the past, but are no longer actively engaged. You want to remind them about your great product.

Proposed idea: We'll do an email campaign. Clients who haven't interacted with you for a while will be eligible to receive this email, and the purpose is to get them to visit your website. (Note that instead of email, we could just as easily use a widget on a website, a letter in the mail, or any other method of communicating with clients.)

The One Size Fits All Method

Your team brainstorms several tactics and decides to run a test to see which one works best. Let's use a simple three-tactic example here:

- Tactic A: no email. This is our control, which we can use to establish a baseline for client behavior;

- Tactic B: an emailed invitation to work 1-on-1 with (in our case) an expert stylist via email to make sure we get you exactly what you want; and

- Tactic C: an emailed promotional offer.

You run this test and find that Tactic B works the best. As such, you decide to scale Tactic B out to all clients, since it is expected to maximize return.

This is an endpoint in many marketing and product pipelines. The team celebrates the discovery of the "best" strategy and now it's time to move on to the next project; Case closed.

Main Limitations with this Approach

- You have no idea how long Tactic B will continue to be the best. Let's say over the next year your product improves and expands, leading to a change in the demographics of your client base. How confident are you that Tactic B is still the best?

- There is no personalization. All clients are receiving Tactic B. Some subsegment of clients likely would have performed better with Tactic C, but by scaling out Tactic B to all clients, these clients did not receive their optimal tactic.

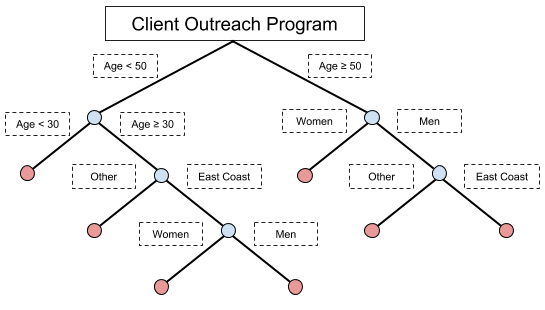

- You are not taking advantage of key pieces of information. Since everyone in this audience was a previous client, you have information on how they interacted with you in the past! To address this, teams frequently build out a decision tree that groups their clients into broad categories (such as by age or tenure with the company). However…

- Using decision trees to group clients into categories leads to unoptimized outreach programs. Each category of clients might get a different tactic, and as new tactics or categories are created, these trees can grow larger and larger. Many of you have seen it: 10+ branch decision trees that try to segment a client base into different categories. When these trees grow too large, not only do they become difficult to manage, but it becomes more and more questionable whether or not you are actually doing what you think you are doing.

Part 2: Multi-Armed Bandits Allows Continuous Monitoring

The above situation is common, suboptimal, and headache-inducing. Developing a testing and implementation strategy with bandits can remove or reduce many of these limitations.

A standard multi-armed bandit is the most basic bandit implementation. It allows us to allocate a small amount of clients to continuously explore how different tactics are performing, while giving the majority of clients the current one-size-fits-all best-performing tactic. The standard implementation updates which tactic is best after every client interaction, allowing you to quickly settle on the most effective large-scale tactic.

To get into more technical detail, a multi-armed bandit is a system where you must select one action from a set of possible actions for a given 'resource' (in our example, the 'resource' is a client). The 'reward' (if a client responds to the offer or not) for the selected action is exposed, but the reward for all other actions remains unknown (we don't know what a specific client would have done if we had sent them a different offer!).

The reward for a given action can be thought of as a random reward drawn from a probability distribution specific to that action. Because these probability distributions may not be known or may change over time, we want this system to allocate some resources to improving our understanding of the different choices ('exploration') while simultaneously maximizing our expected gains based on our historical knowledge ('exploitation'). Our goal is to minimize "regret," defined as the difference between the sum of rewards if we used an optimal strategy and the actual sum of rewards realized.

Mathematically, if we have a bandit with K choices (K arms), we can define a reward for 1 ≤ i ≤ K and n ≥ 1, where i is an arm of the bandit and n is the round we are currently considering.

Each round yields a reward The reward of each round is a function of which arm was selected for the client, and is assumed to be independent of both the rewards from previous rounds and the distributions of the other arms, and only dependent upon the probability distribution associated with the selected arm.

We thus want to minimized our regret, defined as:

, where total number of rounds, maximum reward, and is the reward in round n from selecting arm i.

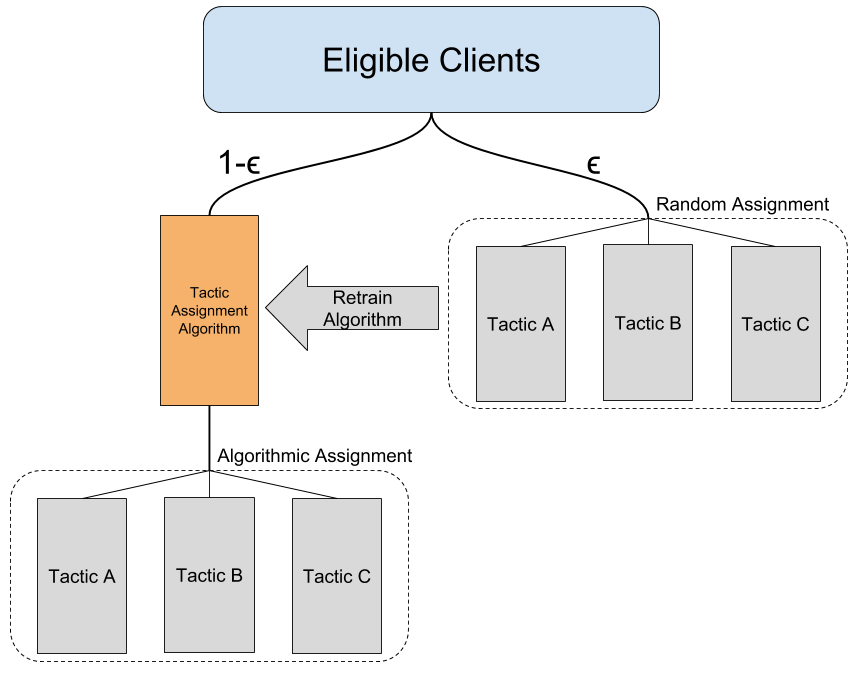

There are numerous strategies that can be utilized to select how clients are allocated to either exploitation or exploration in order to minimize the regret of your bandit. For this article, we will consider the simplest, called the epsilon-greedy algorithm. In the epsilon-greedy algorithm, the best action is selected for 1−ϵ of your audience entering your program, and a random action is selected for the remaining ϵ of your audience. ϵ can be set to any value, depending on how many resources you want to allocate to exploration. For example, if ϵ is set to 0.1, then 10% of your audience is being directed to exploration, and 90% of your audience is being directed to your best tactic. If desired, ϵ can be decreased over time to reduce the total regret of your system. Other popular allocation strategies that can reduce the overall regret of your system include Thompson sampling and UCB1[1][2].

Back to our Example

Let’s get back to our 3-tactic email test, and set up a standard multi-armed bandit. We need to decide to reach out to a client with either Tactic A, B, or C. We are going to use an epsilon-greedy approach and set ϵ=0.1. 10% of our clients will randomly be presented with one of the three tactics. The other 90% will receive whichever tactic is the current top-performer. Each time we give a client a tactic, we update the score for that tactic. We then examine the performance of the different tactics, and re-assign the best-performing tactic to the one with the highest score.

The above animation demonstrates a simple, standard multi-armed bandit to help get you started thinking about how a bandit implementation might look. This example already allows us to continuously monitor how tactics are performing and actively redirects most of our audience to the current "best" tactic, but there is plenty more we can do to improve performance! For example, if we want to further minimize regret, we would want to use a more powerful regret-minimization technique (UCB1, Thompson Sampling, etc.) If we are nervous about our client population changing over time, we can implement a forgetting factor to down-weight older data points. New tactics can be added to this framework in a similar manner.

Part 3: Personalize Outreach with Contextual Bandits

While we have already improved upon our original example, let's take this a step further to get to true personalization.

Contextual bandits provide an extension to the bandit framework where a context (feature-vector) is associated with each client.[3] This allows us to personalize the action taken on each individual client, rather than simply applying the overall best tactic. For example, while Tactic B might perform the best if applied to all clients, there are certainly some clients who would respond better to Tactic C.

What this means in terms of our example is that instead of 90% of our clients being sent the one-size-fits-all best email, these clients instead enter our "selection algorithm." We then read in relevant features of these clients to decide which outreach tactic best suits each client’s needs and results in the best outcomes. We continue to assign 10% clients to a random tactic, because this lets us know the unbiased performance of each tactic and provides us with data to periodically retrain our selection algorithm.

To get started, we need to take some unbiased data and train a machine learning model. Let’s assume we have been running the multi-arm bandit above: because we randomly assigned clients to our different tactics, we can use this data to train our algorithm! The point here is to understand which clients we should be assigning to each tactic, or, for a given client, which tactic gives this client the highest probability of having a positive outcome.

While a multi-armed bandit can be relatively quick to implement, a contextual bandit adds a decent amount of complexity to our problem. In addition to training and applying a machine learning model to the majority of clients, there are a number of additional behind-the-scenes steps that must be taken: for example, we need to establish a cadence for retraining this model as we continue to acquire more data, as well as build out significantly more logging in order to track from which pathway clients are being assigned to different tactics.

Why do we care about which pathway clients received an offer from? If we use an algorithm to assign a tactic to a client, clients with certain characteristics are more likely to be assigned to certain tactics. This is why it is important to have some clients assigned randomly: we can be confident that, in the random assignments, the underlying client distributions are the same for all tactics.

Contextual Considerations

Depending on the regret-minimization strategy, there may be restrictions on the type of model you can build. For example, using an epsilon-greedy strategy allows you to use any model you like. However, with Thompson sampling, using a non-linear model introduces significant additional challenges.[5] When deciding how to approach regret minimization, make sure to take your desired modeling approach into account.

No implementation is perfect, and bandits are no exception. Both multi-armed bandits and contextual bandits are best utilized when we have a clear, well-defined 'reward' – maybe this is clicking on a webpage banner, or clicking through an email, or purchasing something. If you can't concretely define a reward, you can't say whether or not a tactic was successful, let alone train a model. In addition, if you have significantly delayed feedback you will have to do some additional work to get everything running smoothly[4]. Contextual bandits also lead to more complex code, which gives more room for things to break when compared to implementing simpler strategies.

Finally, think carefully about real-world restrictions: for example, while a contextual bandit can support a large number of tactics, if you have very few clients entering the program you are not going to be gaining much information from your random test group ϵ . In this case, it may be wise to restrict the number of tactics to something manageable. Remember though, you can always remove tactics to make room for new ones!

Part 4: Summary and Final Thoughts

Expanding your program from using business-logic-driven decision making to model-based decision making can significantly improve the performance of your client engagement strategies, and bandits can be a great tool to facilitate this transition.

While the example we used involved email, this same pipeline can be applied in a variety of different domains. Other examples include prioritizing widgets on a webpage, modifying the flow clients experience as they click through forms on your website, or many other situations where you are performing client outreach.

If you currently have a single tactic scaled out to all clients and are not gathering any unbiased data, one viable approach to improve this situation would be to first transition to a multi-armed bandit, and then at a later timepoint transition to a contextual bandit. A basic multi-armed bandit can be quick to implement and allow you to begin gathering unbiased data. Eventually, utilizing a contextual bandit in your client engagement strategy will allow you to active adjust to changing client climates and needs, continuously test strategies, and personalize, personalize, personalize!